Bronchial asthma (BA) stands as the world’s most common chronic respiratory disease and both its annual prevalence and treatment costs continue to increase. Asthma represents a chronic airway inflammation disease that involves various cells and their components while chronic inflammation and increased airway responsiveness remain its primary characteristics. Patients with bronchial asthma display repeated wheezing and shortness of breath which may present with cough or chest tightness. The progression of the disease leads to structural changes known as airway remodeling. The etiology of BA is relatively complex. Viral infections trigger patient attacks while wheezing symptoms show over 80% correlation with viral infections. Research has established that both respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus (RV) are known viral causes of bronchial asthma (BA). RSV infection results in more severe BA symptoms than RV infection and can present life-threatening risks. Uncovering how RSV infections lead to BA could establish foundational approaches for BA treatment and management.

RSV

Host cells sometimes merge into giant syncytia to contain viral spread which helps protect surrounding cells from infection thereby delaying the infection’s progression. The non-segmented negative-strand RNA virus RSV exhibits diameters that range from 120 to 300 nanometers.It can replicate in cells and has rod-shaped protrusions. It belongs to the family Pneumoviridae and the genus Orthopneumovirus. The RSV genome can encode a variety of proteins, including three transmembrane proteins and two non-structural proteins (NS1 and NS2). The above key proteins are closely related to RSV infection-induced BA. Among them, F and G proteins are protective antigens of RSV. The former mediates RSV penetration and fusion with the cell membrane, implants the viral RNA chain into the host cell, and induces humoral immunity and cellular immunity. The latter mediates RSV adsorption and induces humoral immunity. G protein is the main component of RSV mutation. SH protein can induce inflammatory response and inhibit cell apoptosis. NS1 and NS2 proteins play a key role in RSV replication and pathogenicity. Winter and spring are the peak seasons for RSV infection to induce BA. Infants, the elderly or immunocompromised people are at high risk of RSV infection, among which infants under 2 years old are susceptible groups. The immune response acquired by the body after RSV infection does not last long and can still be infected again. This is related to the fact that the immune system of infants and young children is not yet fully mature and lacks protective immunity to RSV infection. Many scholars believe that severe RSV infection is closely related to repeated wheezing in infancy. When infants develop lungs infected with RSV they experience alterations in alveolar structure or function which produce lasting effects. RSV infection during early childhood creates a strong link to the development of BA later in adult life. RSV functions as an independent risk factor for BA development but the mechanism through which RSV induces BA remains controversial or contradictory.

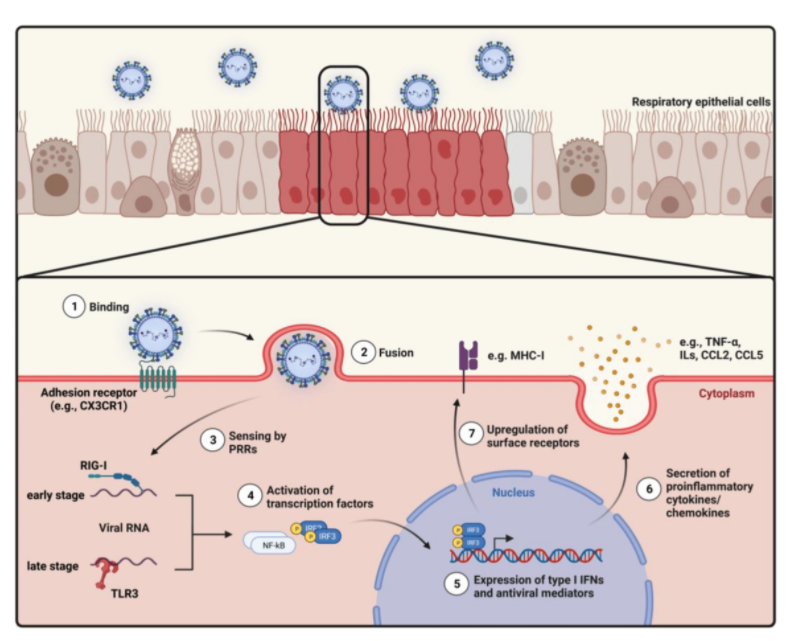

Figure 1. Overview of the intracellular mechanisms in airway epithelial cells (AECs) after respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) entry.

RSV Infection Triggers the Body’s Innate Immune Response

Innate immunity is gradually formed in the long-term evolution of the body. It is the first line of defense against pathogen invasion and is not affected by immune memory. RSV suspended in the air enters the human respiratory tract, attaches to the respiratory epithelial cells and reproduces. A healthy body can rely on innate immune cells and molecules to recognize RSV, quickly activate and effectively phagocytize, kill or eliminate RSV. RSV infection can trigger the body and airway innate immune response. The innate immune response involves actions from monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells alongside eosinophils, innate lymphocytes (ILCs), neutrophils, natural killer cells (NKs) and chemokines. RSV targets nasal epithelial cells to trigger the release of pro-inflammatory mediators that attract immune cells such as monocytes and macrophages along with DCs. Monocytes can play two roles: Monocytes stimulate the production of inflammatory substances. Damage to Th2 cells disrupts the immune system’s balance and functionality. Damaged Th2 cells produce cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 with the help of monocytes. L-13 stimulates Th1 cell activation and differentiation as well as interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production by triggering IL-12 secretion. IFN-γ has an immunomodulatory effect. IL-4 and IL-13 cytokines are essential for the Th2 immune response function. These elements initiate antibody production in B cells and enhance eosinophil activity along with influencing airway epithelial cells which supports Th2 immune responses.

TLRs located on monocytes operate as vital components of innate immune defenses that defend the body from invading pathogens. Binding of RSV F protein to infection sites triggers TLR activation which enables LPS to attach to airway epithelial cells followed by MAPK pathway activation through signaling. MAPK activation triggers inflammatory responses that produce cytokines and chemokines to fight infections but also risks resulting in inflammatory harm.

The G protein of RSV specifically binds to fractalkine (Fkn)-like motifs which then modulates innate immune responses. Fkn represents a crucial element of the CX3C chemokine family with primary expression in endothelial cells, neurons and DCs. The N-terminal membrane-bound chemokine-like domain together with the C-terminal typical chemokine domain allows Fkn to serve as both an adhesion molecule and a chemokine. The expression of IFN-γ and TNF-α remains under control by the motif of Fkn during normal conditions. A mutation or absence of the motif leads to increased levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α during RSV infection which then initiates an inflammatory response.

The RSV SH protein activates inflammatory responses and prevents cell apoptosis from occurring. Intracytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) build multiprotein complexes known as inflammasomes. Innate immunity depends on them because they activate inflammatory responses which helps cause innate immune reactions and inflammation-related conditions. The SH protein from RSV activates inflammasomes that then recruit and initiate caspase-1 activation. The enzyme caspase-1 functions as a critical component in apoptosis while typically existing in the cytoplasm as inactive proenzymes. The active form of caspase-1 transforms many inflammatory mediators into their active states including IL-1β precursor (proIL-1β) and IL-18 precursor (pro-IL-18) to generate active IL-β and IL-18. The excessive inflammatory response does not eliminate RSV while simultaneously damaging airway structures. The SH protein of RSV delays apoptosis through the inhibition of TNF-α signaling. Apoptosis plays a role in repairing airway tissue while delayed apoptosis proves advantageous for airway remodeling.

The NS1 and NS2 proteins of RSV function to block the release of IFN-γ. The NS protein helps RSV replication by blocking IFN-γ’s antiviral effects to avoid host immune defenses as demonstrated by the reduction of RSV replication in cells expressing IFN-γ when the NS gene is lost. The NS gene together with its encoded protein is crucial for RSV replication in cells producing IFN-γ and this finding opens up possibilities for creating new antiviral medications against RSV.

Infection by RSV Impacts How the Adaptive Immune System Responds to Threats

T cells represent one particular lymphocyte subtype and make up between 40% and 60% of the total lymphocyte population. They play crucial roles in immune defense by preventing viral replication through their production and release of cytokines. The immune system relies on DCs as vital elements for its operation. The cells operate in an activated state and move through lymphatic vessels to deliver antigens to nearby lymph nodes. When DCs move into lymph nodes they start T cell responses through initial T cell activation resulting in anti-tumor immunity. Both T cells and dendritic cells work together to manage immune system reactions. DCs can activate T cells and initiate T cell responses. T cells can also affect the maturation and activation state of DCs. One week after RSV infection, the body’s adaptive immune response can be activated, and the cooperation between T cells, DCs, and T-DCs will be impaired. The adaptive immune system cannot produce an effective memory T cell response when responding to RSV infection, and the body’s defense against RSV will decrease. It has been reported that patients with early RSV infection may experience systemic T-cell lymphopenia, especially CD8+ and CD4+, compared with individuals in the recovery period and those who are not infected, and T-cell counts are negatively correlated with the severity of RSV infection. The function of DCs in the pathogenesis of BA is very complex, related to the subpopulation of DCs, and also depends on the stage of DCs in the immune response and the localization of the airway. Because it is difficult to obtain lung tissue from patients with BA attacks, it is quite difficult to conduct functional studies on DCs subpopulations.

F and G proteins are important antigens on the surface of RSV and can be recognized by the body’s immune system. When RSV infects the human body, these antigens will stimulate and induce the body to produce adaptive immunity, especially B lymphocyte responses. B cells differentiate into plasma cells after being stimulated by antigens. Plasma cells then synthesize and secrete RSV-specific antibodies, mainly including immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin G (IgG), and immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgA is responsible for the defense of the mucosal surface. IgA and IgG jointly prevent the virus from interacting with airway epithelial cell receptors, blocking the invasion and replication of RSV, or promoting RSV neutralization, conditioning, and clearance by phagocytes, reducing the number of RSV in the body. IgE can bind to FcεRI of mast cells and eosinophils. When RSV enters the body again, it binds to IgE and activates FcεRI again. The activated FcεRI can release a large amount of mediators such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and histamine, inducing bronchial smooth muscle spasm and leading to BA. Because IgE is an important mediator of local mast cell activation, and Omalizumab can bind to the third constant region of IgE, some studies have suggested that Omalizumab be used to prevent RSV infection in BA. Some scholars have raised objections to this. In 15 BA patients, no IgE antibody was observed to react with any tested antigen, suggesting that these BA patients had low IgE levels. However, this cannot rule out the occurrence of Th2 response, because Th2 cells can also participate in immune response through other mechanisms, such as promoting the activation and proliferation of eosinophils.

Given the high variability and glycosylation characteristics of RSV, the glycosylated RSV protein has better stability and activity. RSV can weaken the host adaptive immune system by relying on the immune escape effect of G protein and the inhibition of DCs function by RSV NS1 and NS2 proteins: 1) By binding to RSV-specific IgG protein, the serum concentration of IgG is reduced; 2) RSV F and G proteins can reduce T cell function by inhibiting mitosis-induced T cell proliferation; 3) DCs differentiate and mature from monocytes, interact with and activate T cells. RSV NS1 and NS2 proteins can inhibit the differentiation and maturation of DCs monocytes and affect their interaction with T cells, resulting in T cells unable to obtain sufficient stimulation to form memory. Therefore, even if BA patients recover, the body is in a weak adaptive immune state, and the patient can be infected with RSV again in a short period of time.

Conclusion

In summary, RSV infection is considered to be an important cause of BA. BA is a disease characterized by airway hyperresponsiveness and chronic airway inflammation. Both innate immunity and adaptive immunity play a role in the immune regulation mechanism of RSV infection-induced BA. Patients with BA who do not respond to conventional treatment can choose biological agents targeting IgE, TSLP, IL-5, NGF, etc., which may help improve symptoms.

| Cat. No | Product Name | Source/Host | |

| DAG-WT1165 | Recombinant RSV PreF glycoprotein F0 | HEK293 cells | Inquiry |

| DAG-WT1180 | Recombinant RSV PostF glycoprotein F0 | HEK293 cells | Inquiry |

| DMAB-JXL23114 | Anti-RSV-F Reference Antibody (pallvizumab) | Human | Inquiry |

| DMAB-JXL2372 | Anti-RSV Pre-F Monoclonal Antibody, clone D25 | Human | Inquiry |